Luther the Reformer

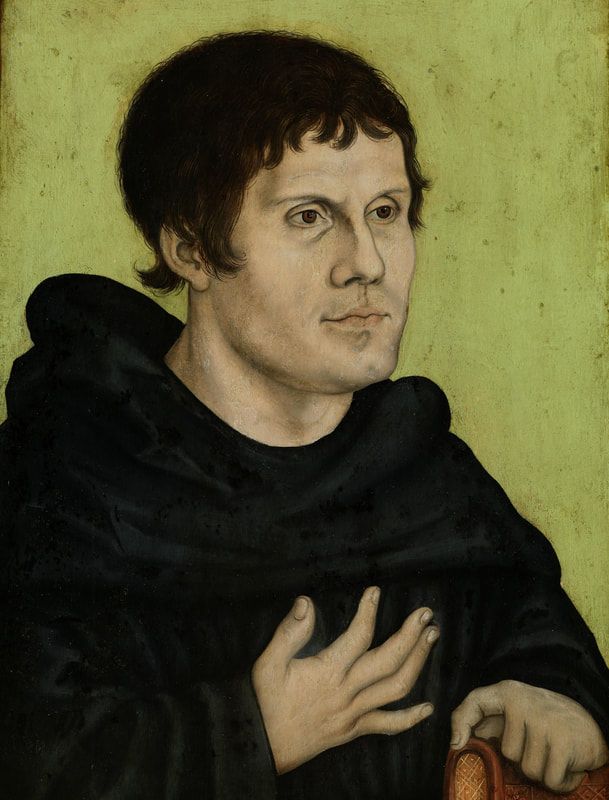

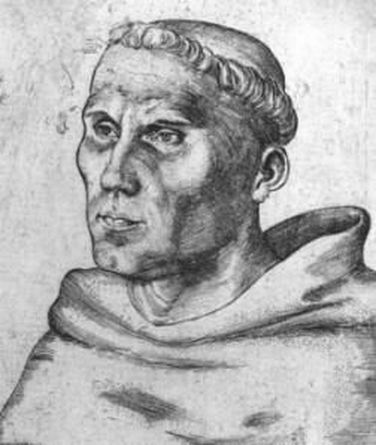

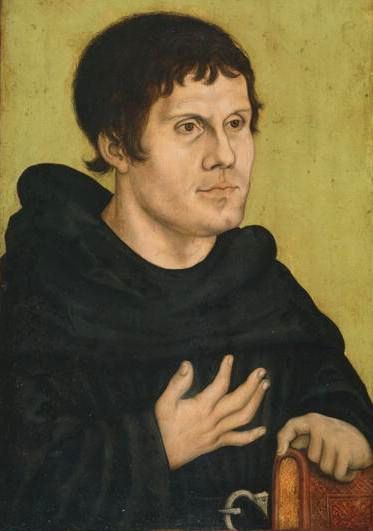

1517 was a pivotal year in Martin Luther's life. As Luther approached his 34th birthday in November of 1517, he had no idea that the actions he was about to undertake would transform him from obscure monk, preacher and professor of biblical studies at tiny Wittenberg University to church reformer. It was not a calling he sought.

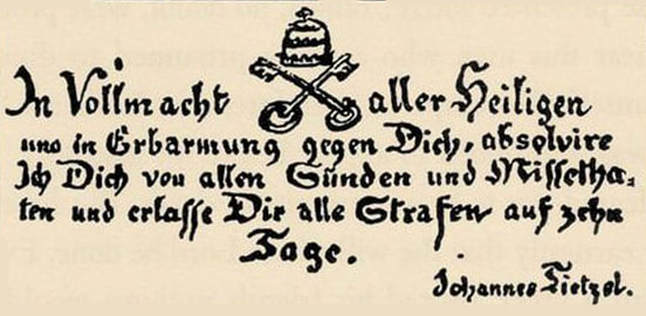

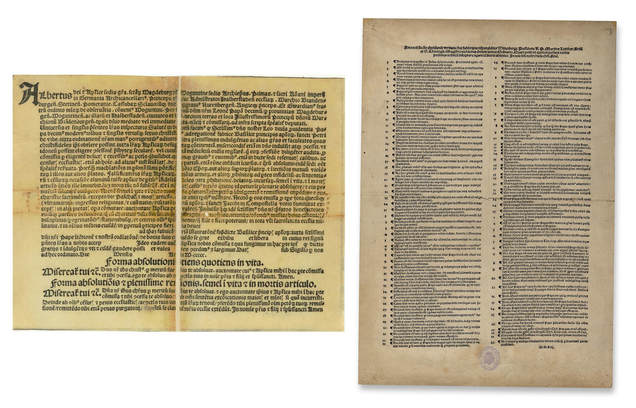

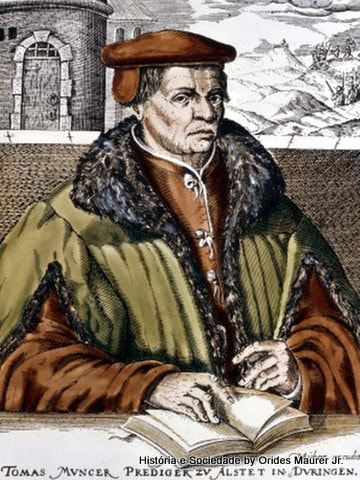

Indulgences: Buying Souls1517 (Luther age 33) - Archbishop Albrecht commissioned Dominican monk Johann Tetzel, an experienced indulgence seller since 15o3, to preach the so-called Peter indulgences in the dioceses of Meissen, Magdeburg and Brandenburg. His court theologians even prepared a booklet for preachers, the Instructio Summaria (Summary Instruction) which described the limits and benefits of the indulgences:

From Albrecht, Archbishop of Magdeburg and Mainz, Primate and Chancellor of the Holy Roman Empire in Germany, Elector, Administrator of the Churches in Halberstadt, Margrave in Brandenburg, etc. To all who read this letter: Salvation in the Lord.

1517 (age 33) - Upon his promotion Tetzel began selling indulgences from town to town. But, he ran into difficulty almost immediately. For one thing, the Elector Frederick the Wise of Saxony, who controlled large portions of both Thuringia and Saxony, prohibited sales in his territories to eliminate competition with in his own burgeoning collection of relics in Wittenberg and to prevent the drain of gold from his lands. Additionally, sales in those places where Tetzel was permitted to preach were slow. In early 1517, Tetzel preached in regions close to Saxony but controlled by friendly rulers.

January 1517 - Tetzel took his show to Eisleben (Luther’s birthplace, seventy miles southwest of Wittenberg); in March he was in Halle, where Albrecht himself resided (fifty miles to the southwest); then in Zerbst (twenty-seven miles west, a 9-hour walk); and finally on Good Friday, April 1o, in Jüterbog (only twenty-three miles northeast, an 8-hour walk). Tetzel was a showman, a medieval P.T. Barnum or Buffalo Bill Cody. According to contemporary accounts he was met at a town's gate by important government and church officials and escorted to the main church. Trumpeters, an armed guard, bells, candles and flags joined the procession. All other preaching was halted so citizens would pay full attention to Tetzel and the indulgences he offered. Staging his show, the monk displayed a brass-bound chest, a stack of printed indulgences and a banner with the papal crest attached to an enormous cross. Tetzel banged a drum and launched into a chilling description of souls writhing in purgatory:

Listen to the voices of your dear dead relatives and friends, saying, Pity us. Pity us. We are in dire torment from which you can redeem us for a pittance. Will you delay our promised glory? To further entice his gullible listeners to make purchases he devised a catchy slogan:

As soon a coin in coffer rings, the soul from purgatory springs.

Indulgence chest, 16th century with a padlock from 20th century, displayed at the Minneapolis Institute of Art in 2016. Trunks like this were used by Johann Tetzel and other indulgence preachers to collect money from those who wanted a reduced time in purgatory. To Martin Luther this was a corrupt, misleading and non-biblical practice.

Some of Luther's parishioners we're among Tetzel's customers in Zerbst and Jüterbog, the nearest towns to Wittenberg where Tetzel was allowed to preach indulgences. Luther, the parish priest, noticed fewer people coming to confession. They claimed that after purchasing Tetzel's indulgences they no longer needed to repent to be forgiven of their sins. After hearing what Tetzel said in his sermons about indulgences, Luther began to investigate the issue more carefully. He preached against indulgences several times that year, explaining that true repentance was better than purchasing an indulgence.

April to October 1517 - Luther presumably began writing his 95 Theses, expressing his objections to the practice of selling indulgences. He was merely using a means by which other scholars brought issues to the attention of others.

Hammer Blows...or not?

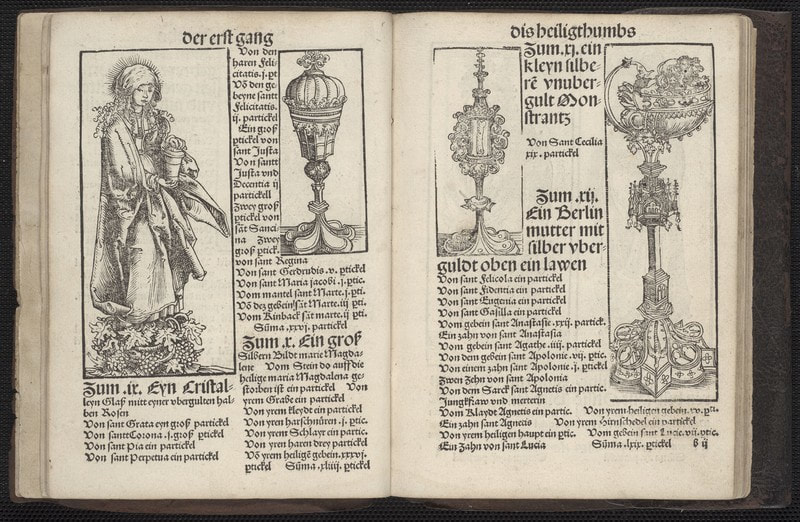

October 31, 1517 (eve of All Saints Day) - Elector Frederick placed his huge collection of reliquaries on display in Wittenberg's All Saints Church (aka Castle Church). Reliquaries were elaborate precious-metal pieces made by artists to enshrine holy objects. Frederick's Castle Church housed one of the largest collections of relics in Europe. In the Middle Ages, treasured relics at sites of pilgrimage were regarded as holy items. Those who paid to venerate the thousands of items in Frederick's collection were promised indulgences granting a significant reduction of time in purgatory. The event greatly benefited the Elector financially, and helped support his fledgling university. Additionally, pilgrims could purchase reliquary books, i.e. catalogs of relics, when they came to the Castle Church. The books acted as souvenirs of their pilgrimage, aids for meditation and prayer, and even as advertisements for the display of the relics and the pilgrimage site. The illustrations by Lucas Cranach in this Wittenberg Reliquary Book paint a vivid picture of the sheer number of objects in the Wittenberg treasure of relics, which had been collected by Elector Frederick the Wise. At the same time, it was intended to show the abundance of the Elector's political, religious and intellectual power. On or before October 31, 1517 - Luther, who was acutely aware of church authority, sent a letter to Albrecht of Brandenburg, the young Archbishop of Mainz (his "boss"), then residing in Halle, 50 miles southwest of Wittenberg, objecting to the sale of indulgences:

Under your most distinguished name, papal indulgences are offered over all the land for the construction of St. Peter ... I do not so much complain about the quacking of the preachers which I haven't heard, but I bewail the gross misunderstanding among the people which comes from these preachers ... Evidently the poor souls believe that when they have bought indulgence letters they are assured salvation. They are likewise convinced that souls escape purgatory as soon as they have placed a contribution in the chest With his letter, Luther enclosed a copy of his Treatise on Indulgences, along with his Disputation of Martin Luther on the Power and Efficacy of Indulgences, better known as the 95 Theses.

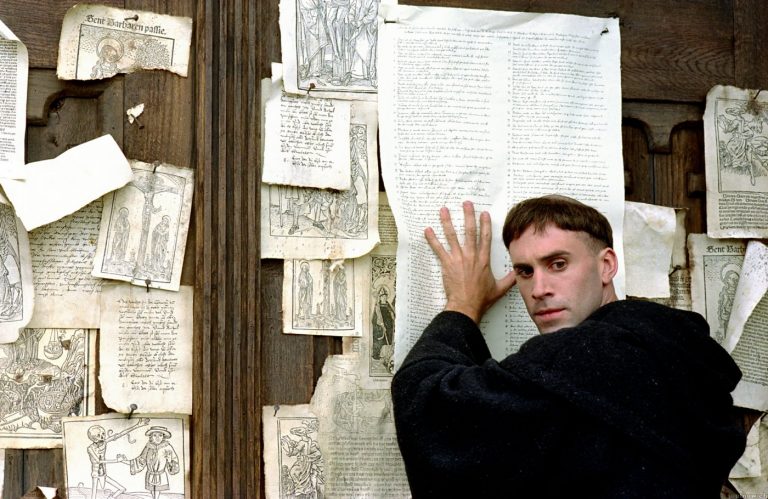

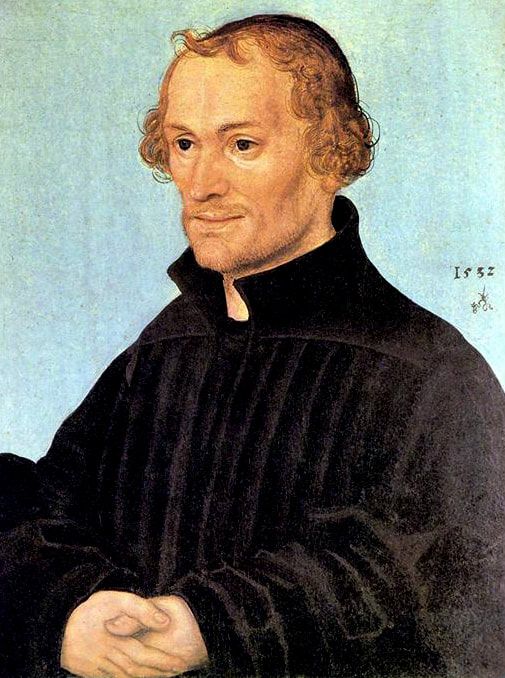

Luther assumed that Albrecht would want to know about church abuses in his jurisdiction and was thoroughly convinced that after he read his theses that the scope of the scandal of indulgences would reach him and he'd kick out all the indulgence sellers. According to Luther he was unaware at the time of the deal Albrecht had cut with the pope and that he had a vested interest in the ongoing selling of indulgences. October 31, 1517 (Luther age 28) - According to a preface to the second volume of Luther's Latin Works, written by Philipp Melanchthon in June 1546, Luther nailed a copy of his 95 Theses to the door of the Castle Church in Wittenberg on the eve of All Saints Day.

Scholars have questioned Melanchthon's account, noting that Luther's collegue didn't arrive in Wittenberg until 1518, so wasn't an eyewitness. Nearly 30 years had passed by the time Melanchthon wrote, and few if any eyewitnesses existed to verify his statement. We are further handicapped because Luther never mentioned any public posting of his theses, not in his own writings reviewing the beginning of the controversy, nor in his later Table Talk. Luther did recall preaching to the people about grace and remission of sins against the shallow proclamations of indulgence hawkers. Undoubtedly Melanchthon and Luther had countless conversations not recorded elsewhere, so that Melanchthon could simply have reported what Luther had told him, namely, that on October 31, 1517, he posted a copy of his 95 Theses on the Castle Church door. Furthermore, Luther seems to also have held private discusions with other associates and to have sent copies of the theses to friends. Also, a handwritten note recorded before Luther's death in a book owned by Georg Rörer (1492–1557), Luther's faithful scribe who preserved many of his lectures and sermons, mentions how the Theses were published on all the church doors in Wittenberg. But none of this has the visual impact of a robed monk hammering a set of theses to church doors and calling for a debate. Luther scholars have rushed to defend the historicity of the hammer blows stating that posting announcements on church doors was regularly used for exactly the kind of announcement Luther made: Out of love for the truth and from desire to elucidate it, the Reverend Father Martin Luther, Master of Arts and Sacred Theology, and ordinary lecturer at Wittenberg, intends to defend the following statements and to dispute on them in that place. Therefore he asks that those who cannot be present and dispute with him orally shall do so in their absence by letter. But whether the "hammering" event happened on a specific date — or at all — is not the point. In 21st century terminology the theses "went viral." They were translated from their original Latin, the language of scholars, diplomacy and the church, into German, the language of everyday people, and given to a printers for publication and distribution. The presses couldn't print the Theses fast enough. In December 1517 printed editions of the Theses -- in the form of broadsheets and pamphlets -- appeared in Basel, Leipzig and Nuremberg. Later, Luther's colleague, Friedrich Myconius, wrote:

Hardly 14 days had passed when these propositions were known throughout the German-speaking lands and within four weeks almost all of Christendom was familiar with them. As a result, an obscure Augustinian monk, a nobody in a backwater university in a little town, become a household name. It was one of the first events in history profoundly affected by a revolutionary new technology: the printing press with movable metal type, invented by Johannes Gutenberg around 1439. Luther commented:

I only intended to submit [the Theses] to a few close friends for discussion ... I wanted to publish them, only if they met with approval. But now they are being printed and spread everywhere far beyond my expectation ... Still, the spread of my Theses shows what people everywhere really think of Indulgences. Key points of Martin Luther's 95 Theses (debate points):

Luther's Theses were sharp, witty and to the point. They made Germans everyhere think, laugh and nod their heads. Here are some examples:

The doors of Wittenberg's Castle Church today. The church was seriously damaged by fire in 1760 after a French bombardment during the Seven Years War. The church was quickly rebuilt, and later (1885-1892) further restored. In 1858, to commemorate the 375th anniversary of Luther's birth, the doors were replaced with ones of bronze with the original Latin text of the 95 Theses.

October 31, 1517 - Elector Frederick the Wise of Saxony told his brother, Duke John, of a dream he had the previous night. John was then residing at his palace in Schweinitz, 33 miles northwest of Wittenberg. The truth of the dream, recorded by all the chroniclers of the time, is not in doubt, however we may interpret it:

Brother, I must tell you a dream which I had last night, and the meaning of which I should like much to know. It is so deeply impressed on my mind, that I will never forget it, were I to live a thousand years. For I dreamed it thrice, and each time with new circumstances, Duke John:

Is it a good or a bad dream? Elector Frederick:

I know not; God knows. Duke John:

Don’t be uneasy at it; but be so good as tell it to me. Elector Frederick said:

Having gone to bed last night, fatigued and out of spirits, I fell asleep shortly after my prayer, and slept calmly for about two and a half hours; I then awoke, and continued awake until midnight, all sorts of thoughts passing through my mind. Among other things, I thought how I was to observe the Feast of All Saints. I prayed for the poor souls in purgatory; and asked God to guide me, my counsels and my people according to truth. I again fell asleep, and then dreamed that God sent me a monk, who was a true son of the Apostle Paul. All the saints accompanied him by order of God, in order to bear testimony before me, and to declare that he did not come to contrive any plot, but that all that he did was according to the will of God. They asked me to permit him to write something on the door of the church of the Castle of Wittenberg. This I granted through my chancellor. Thereupon the monk went to the church, and began to write in such large characters that I could read the writing at Schweinitz. The pen he used was so large that its end reached as far as Rome, where it pierced the ears of a lion that was crouching there, and caused the triple crown upon the head of the Pope to shake. All the cardinals and princes, running hastily up, tried to prevent it from falling. You and I, brother, wished also to assist, and I stretched out my arm — but at this moment I awoke, with my arm in the air, quite amazed, and very much enraged at the monk for not managing his pen better. I collected myself a little; it was only a dream. We will not be able to know for some time — not until the things to which it relates have taken place. Therefore we should leave it in God's hand Duke John asked a court adviser about the meaning of the dream, and he replied;

We will not know the meaning of this dream for some time — not until the things to which it relates have taken place. We should therefore leave it in God's hand. Duke John said:

I am of the opinion that it is not fit for us to annoy ourselves in attempting to discover the meaning. God will overrule all for his glory. To which Elector Frederick replied:

May our faithful God do so; yet I shall never forget the dream. I have, indeed, thought of an interpretation, but I keep it to myself. Time, perhaps, will show if I have been a good diviner. Luder/Ludher becomes Luther

About the time Martin authored his 95 Theses, he briefly changed his ancestral surname from Luder to Eluetheros, Greek for "free," reflecting his new-found understanding of the Gospel. Luder or Ludher, it seems had some negative meanings: hussy, whore. Soon, however, he dropped all but the "th," and inserted it into his birth name, calling himself "Luther," a more proper sounding name in academic circles. In fact, he signed his "indulgence letter" to archbishop Albrecnt with his recently adopted name, "Martinus Luther." War of the Pamphlets: And the Winner Is... December 1, 1517 - Archbishop Albrecht forward the copies of Luther's 95 Theses and his Treatise on Indulgences on to the faculty of the University of Mainz, asking their opinion as to the orthodoxy of the documents. Later that month the Mainz professors sent a brief report and advised the Archbishop to send Luther's writings on to Pope Leo in Rome—which the Archbishop had already done. January 20, 1518 - Three hundred Dominicans met at their regional chapter meeting in Frankfurt for a disputation (debate) concerning Luther's 95 Theses. In an attempt of refute Luther's theses indulgence preacher Johann Tetzel presented 106 Theses written by Konrad Koch (also known as Konrad Wimpina), a fellow Dominican and professor at Frankfort University. When Luther's supporters received the document they burned it in protest. At first Pope Leo tried to ignore what was happening in Wittenberg. He reportedly commented: Brother Martin is a man of fine genius, and this outbreak is a mere squabble of envious monks. Still later he said,

It is a drunken German who wrote the Theses; when sober he will change his mind. January–March, 1518 – In response to Tetzel’s 106 Theses, Luther wrote Resolutions to the 95 Theses to further clarify his understanding of indulgences and penance and sent it to Pope Leo X. However, it was not published until early summer 1518. Luther also was increasingly aware of a campaign waged against him by Dominican preachers, who attacked him from various pulpits as a heretic and one who deviated from established Church practice.

I have heard evil reports about myself, most blessed Father, by which I know that certain friends have put my name in very bad odor with you and yours, saying that I have attempted to belittle the power of the keys and of the Supreme Pontiff. Therefore I am accused of heresy, apostasy, and perfidy, and am called by six hundred other names of ignominy. My ears shudder and my eyes are astounded. But the one thing in which I put my confidence remains unshaken -- my clear and quiet conscience. Moreover, what I hear is nothing new ... But you will deign, blessed Father, to hear the true case from me, though I am but an uncouth child. February 1518 – It took Pope Leo three months to realize that he had to act, and he instructed the victor-general of the Augustinian Order in Rome, Gabriel Venetus, to quiet the restless monk. Venetus ordered Luther to be seized, “bound in chains, fetters and handcuffs” and sent immediately to Rome, but Elector Frederick intervened on the principle that Germans were not to be tried in foreign courts.

March 1518 – Pope Leo commission Silvester Mazzolini, known as Priero or Prierias after his birthplace (Priero, Italy), to respond to Luther's 95 Theses. Mazzolini, a monk in the influential Dominican Order, is credited with being the first theologian who publicly attacked Luther in writing over what the Catholic Church called his subversive errors. In his Dialogue Mazzolini argued that the pope is the head of the church, that the pope cannot err, that anyone who denies the teaching of the church and the pope is a heretic, and that the church can establish customs in regard to faith and ethics. March (latter part) 1518 – A bookseller arrived in Wittenberg to sell printed copies of Tetzel’s 106 Theses. University students, enthusiastic supporters of Luther, took the copies and burned them in the town square. April 25, 1518 (age 34) – A few months after posting his 95 Theses, Martin Luther was invited to Heidelberg by the Augustinian Order, to which Luther belonged. The head of the order in Germany, Johann Staupitz, Luther's friend and spiritual father, called for a formal meeting attended by the leadership of the order, in which Luther would be given a chance to articulate his views. His opponents hoped that he would be silenced, but Staupitz, wanted to give Luther a fair hearing, In preparation for the meeting, which was held at the lecture hall of the Augustinian order, Luther wrote 40 theses, none of which mentioned such controversial issues as purgatory, the infallibility of the Pope and indulgences. Rather, he presented his views on sin, free will and grace. Two of the debate points Luther presented at Heidelberg:

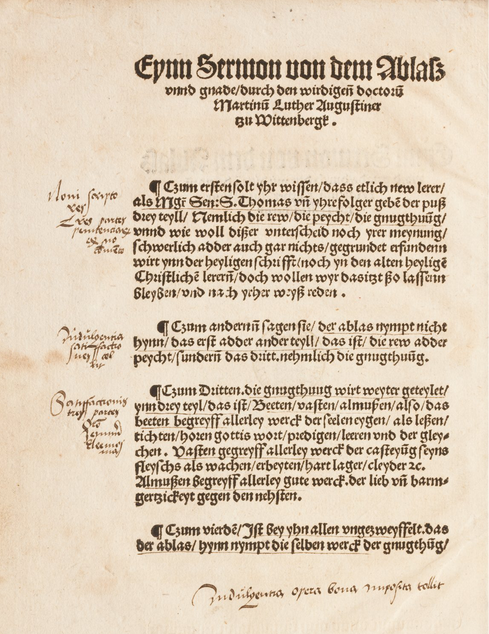

Along with the Augustinian monks, members of the university in Heidelberg also were present at the debate. While many of the older professors criticized Luther's ideas, the students and younger members of the university were enthralled by the fiery Luther. Many of them later became friends and supporters, who spread the Lutheran ideas, mainly in southern Germany. Due to their influence, the Reformation was introduced relatively early in this region. Among them was Martin Bucer from Strasbourg, who became an avid follower. As a result of the disputation, John Eck proposed a debate between himself and representatives of Luther's views (which was held in Leipzig from June to July 1519. See below). April 1518 - Luther published his Sermon on Indulgences and Grace (Eynn Sermon von dem Ablasz und Gnade), an 8-page pamphlet, to make his 95 Theses easier to understand by non-scholars. It was written in German rather than the scholarly Latin, avoiding regional vocabulary to ensure that his words were understood by all Germanic peoples (which included not only readers but also illiterate listeners as well). Luther reduced complicated theological concepts, such as penance or indulgences, to their simplest terms. He stressed good works and sincere repentance over indulgences, which he criticized as non-scriptural. He blasted the Catholic clergy for wasting money on St. Peter's Basilica when it could be better spent on the poor in their own neighborhoods. An instant hit, it was reprinted 14 times in 1518 alone, in print runs of at least 1,000 copies each. Many regard it as the true starting point of the Reformation. The sermon swept through the major centers of the Holy Roman Empire, and the broader reading public first came to know something of Luther. It has been described as "the world's first printed best-seller." No one can defend the position with with any passage from Scripture that God's righteousness desires or demands any punishment or satisfaction from sinners except for their heartfelt and true contrition alone with the condition that from that moment on they bear the cross of Christ and practice works, but not as imposed by anyone. For this is what God said through Ezekiel: "But if a wicked person turns away from all the sins they have committed and keeps all my decrees and does what is just and right, I will no longer remember their sins." (Ezekiel 18:21 together with 33:14-16) This was just the beginning of a media war between Luther and various opponents. And Luther and his colleagues soon proved they were as comfortable with the modern technology of their time -- the printing press with moveable type -- as a teenager is with a smartphone today.

Indulgence preacher Johann Tetzel acted quickly. A month after Luther's Sermon on Indulgences and Grace was published, he wrote Vorlegung gemacht von Bruder Johan Tetzel Prediger Ordens Ketzermeister (Rebuttal Made by Brother Johann Tetzel, the Order of Preachers' Inquisitor of Heretics), his attempt to refute Luther's popular sermon. Like Luther, Tetzel wrote in German, attempting to show how heretical Luther's statements were and warning Christians not to be seduced by what he wrote. He first quoted twenty “articles” or theses in Luther's "Sermon" verbatim, then attempted to systematically rebut them. For example:

The fifth erroneous article of the sermon reads as follows: In contrast to Luther's sermon, Tetzel's Vorlegung was far less popular. No one reprinted it in his lifetime (he died in 1519). Although it was reprinted in a few sixteenth-century editions of Luther’s collected works, it has remained little noticed and not easily accessible, Only three extant copies are known today. ++ Online translation of Tetzel's Vorlegung

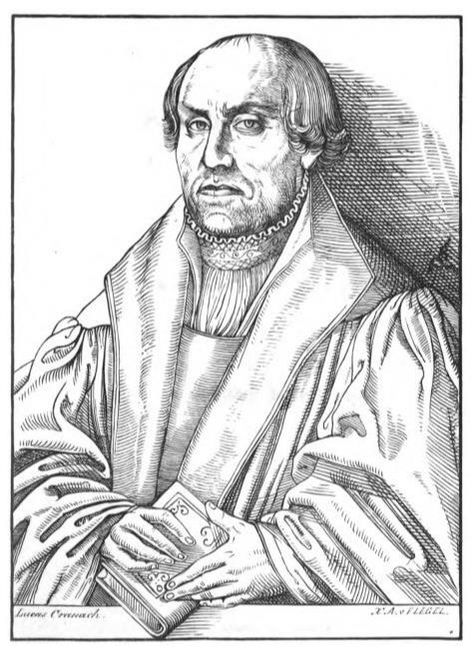

End of April/beginning of May 1518 - Luther called Tetzel’s Vorlegung “an unparalleled example of ignorance” and producesd a second printed response: A Defense of the Sermon on Papal Indulgence and Grace (Eine Freiheit des Sermons Päpstlichen Ablass und Gnade Belangend). Also a best-seller, it was reprinted 11 times between 1518 and 1520. May 1518 - Tetzel issued another rebuttal, 50 theses in Latin, with himself as the author. While he discussed indulgences, his emphasis was on the authority of the Church. The Rebuttal was well-structured; showed an understanding of Scripture and Catholic doctrines. However, this was his last publication. Later that year he retired to a monastery in Leipzig, deserted by the public, broken in spirit and in ill health. Papal ambassador Carl von Meltitz, who has since been discredited, wrote numerous accusations against him, further scandalizing his already damaged reputation. May 30, 1518 - Luther wrote a letter to Christoph von Scheurl, town clerk of Nurnberg: As you are surprised that I did not send [the 95 Theses] to you, my purpose was not to publish them, but first to consult a few of our associates and neighbors about them, then either destroy them (if condemned) or publish them (if approved). But now they have been printed again and again and circulated far beyond my expectation. August 1518 - Wittenberg University was allowed to add seven chairs to its faculty. The chair in Greek was awarded to then 21-year-old Philipp Melanchthon, who earlier that year published a Greek grammar that was to remain in constant demand as a textbook for many decades. It was "subsequently used for 200 years, even in Catholic schools." At the time he came to Wittenberg it was considered a back-country village with mud streets and a severe climate, with a second-rate university. Despite many opportunities to serve at other universities, he called Wittenberg home for the remaining 42 years of his life. He became Luther's close friend and collaborator. Luther said of him:

I have been born to war, and fight with factions and devils; therefore my books are stormy and warlike. I must root out the stumps and stocks, cut away the thorns and hedges, fill up the ditches, and am the rough forester to break a path and make things ready. But Master Philipp walks softly and gently, tills and plants, sows and waters with pleasure, as God has gifted him richly. August 5, 1518 - Emperor Maximilian I denounced Luther as a heretic.

August 1518 – Pope Leo again turned to his adviser, Dominican monk Sylvester Mazzolini (aka Prierias), requesting that he denounce Luther's 95 Theses. Mazzolini wrote: A Dialogue against Martin Luther's Presumptuous Theses Concerning the Power of the Pope, which focused on Luther's questioning the pope's authority rather than his complaints about indulgence preaching. He said of Luther's Theses that they bite like a cur (a mixed-breed dog). He argued that the pope was the head of the church, that he could not err and that anyone who denied the teaching of the church and the pope was a heretic. August 1518 - Luther simply dismissed Mazzolini's Dialogue. He republished it with an introduction, calling it supercilious, thoroughly Italian and in agreement with the teachings of Thomas of Aquinas, a 13th century Dominican monk and theologian. August 7, 1518 - Luther was summoned to Rome within sixty days to answer charges against him. August 23, 1518 – Pope Leo demanded that Elector Frederick "the Wise" of Saxony deliver up the "child of the devil." Again, Elector Frederick intervened on Luther's behalf, asking that he be allowed to meet with the Pope's representative at the governing council (Diet) at Augsburg in southwestern Germany rather than travel to Rome. Frederick took this action because he felt it was his responsibility as a prince to ensure his subject was treated fairly. Pope Leo acceded to Frederick's wishes because he needed German financial support for a planned military campaign that he hoped to sponsor against the Ottoman Empire—whose forces were poised to invade central Europe from Hungary—and because Frederick was one of the seven electors who would choose the successor of the ailing Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian I. Pope Leo had a vital interest in the outcome of this election. Summer 1518 - Legal proceedings began against Luther for his criticism of indulgences and an order was issued for him to stand trial in Rome. However, Rome lifted the requirement, paving the way for Luther to be interogated on German soil.

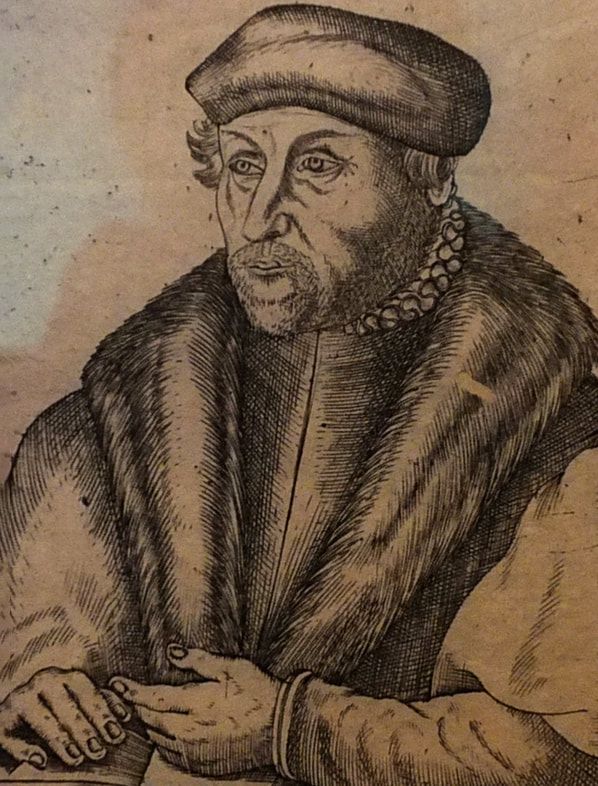

Cardinal Cajetan vs. Luther August 23, 1518 - Pope Leo X ordered his representative, Thomas de Vio, called Cajetan for his hometown of Gaeta, to meet with Luther at the governing council (Diet) at Augsburg in southwestern Germany, and demand he retract his position on indulgences. Cajetan was well thought of in the Roman Catholic Church. When Luther was invited to meet with him it was the first time since the conflict began that he believed that he had the opportunity to meet with someone who could understand the biblical basis for his provocative theses. But the cardinal was a steadfast opponent of the Reformation. October 12-14, 1518 - Their three meetings on three consecutive days began with Luther showing great respect toward the cardinal but their discssions soon turned contentious. The cardinal reminded Luther that the Pope was the interpreter of Scripture and that he was above any council, above everything in the Church. Luther explained that Peter, who was considered the first Pope, was rebuked by Paul and was thus not infallible, then surely any successor to Peter was not infallible. The hearings were made more difficult by the fact that neither had great respect for the other. After the meetings the frustrated cardinal complained to Luther's superior, John Staupitz, "His eyes are as deep as a lake, and there are amazing speculations in his head." Luther remarked that Cajetan was "an evasive, obscure and unintelligible theologian." He wrote home that the cardinal was no more fitted to handle the case than an ass to play on a harp..

Luther remained in Augsburg for another week awaiting some sort of decision, but when rumors reached him that Cajetan was planning to arrest him and taken to Rome for further examination, he fled on horseback at night. Disguised in a long mantle, barefooted and unarmed, Luther rode until the evening of the next day. He dismounted and fell helpless on a bed of straw. At Gräfenthal, about 130 miles south-southwest of Wittenberg, he was overtaken by count Albert of Mansfeld, who laughed heartily at Luther's horsemanship, and insisted on having him as his guest. On the one-year anniversary of posting his 95 Theses he arrived in Wittenberg a hunted man and placed himself under the protection of Elector Frederick III. Catejan now pressured Frederick to have Luther either arrested and sent to Rome or banished from his territories, but Frederick balked. Instead, he wrote to the emperor requesting that Luther's case either be dropped or heard before judges in Germany. November 9, 1518 - Pope Leo X issued the Papal bull, Cum Postquam ("When After"), clarifying the church's doctrine of indulgences. Although it ended some of the worst abuses, It directly contradicted Luther's position by affirming that the pope had complete power to absolve temporal punishment through indulgences. December 18, 1518 (Luther age 34) - Luther was ready to go into exile. But Elector Frederick chose not to banish him, despite requests by the Pope (via his representative Carl von Miltitz) to do so. Instead, Frederick wrote a letter to Cardinal Catejan informing him that he would only send Luther to Rome "after he has been convicted of heresy." He urged that Luther be given an opportunity to debate his interpretation of Scripture and submit it to a university for decision. "He should be shown in what respect he is a heretic and not condemned in advance," wrote Frederick. whose views no doubt reflected those of most Germans. One writer of the period reported that he polled people in inns and found that three out of every four persons he talked to supported Luther. January 4, 1519 (Luther age 35) – For reasons unknown Pope Leo chose to attempt diplomacy before taking harsher actions against Luther. He sent Miltitz to meet with Luther in Altenburg. During his journey Miltiz discovered a wide-spread and growing sympathy for Luther among the people, January 5-6, 1519 – Carl von Miltitz met with Luther in Altenburg. His plan was to ease tensions by placing the blame for much of the indulgence controversy on the Indulgence preacher Johann Tetzel. He even arranged for a hearing with Tetzel that never came to pass because it was made without the approval of Cardinal Cajetan, who supervised Miltitz’s mission, but had left Germany prior to his arrival. In extended conversations with Luther, the two negotiated a tentative settlement. Luther would remain silent on the indulgences, write a conciliatory letter to the Pope and write and publish a tract supporting papal authority. Luther's silence was contingent on the silence of his opponents. Johann Tetzel and Albrecht of Mainz would be disciplined and Luther was allowed to make it plain that he would not recant his position.

Miltitz later met with Luther in Liebenwerda (October 1519) and in Lichtenburg, near Wittenberg (October 1520), but both meetings were fruitless. As for Luther's agreement to keep silent, his participation in the Leipzig Debate in 1519 and his three major treatises published in 1520, ended all hope of reconciliation. January 12, 1519 - Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian I died. In choosing his successor the German electors preferred one of their own. But they agreed to accept the head of one of the great powers, either Francis I of France or Charles I of Spain. The pope objected to both on the grounds that the choice of either would upset the balance of power upon which the church's security rested. Instead the pope preferred Elector Frederick of Saxony, and Luther was his prized professor. Given this circumstance, the pope had to tread lightly until the election was settled. March 3, 1519 - Luther wrote a conciliatory letter to Pope Leo X following his January 6 meeting with Carl von Miltitz:

March 13, 1519 – Luther wrote Georg Spalatin, Frederick the Wise's adviser:

I know not whether the Pope is Antichrist himself, or his apostle; so wretchedly is Christ corrupted and crucified by him in the Decretals.

June-July 1519 - In Leipzig, Johann Eck, a highly respected Dominican friar and a defender of Catholic doctrine, challenged Luther's colleague Andreas Karlstadt to a debate on the issues of free will and grace. It took place at Leipzig's Pleissenburg Castle.

It was conducted in the presence of George, Duke of Saxony, an opponent of Luther. The 18-day debate between two prominent universities drew hundreds of students. Initially, Luther was asked to particpate, but Duke George wouldn't provide him with a letter of safe conduct. Instead, he came as a spectator under the safe conduct given to Karlstadt.

Eck was a man of great learning; he had a good memory and was ready in speech. But, he was overconfident, conceited and boisterous. He looked more like a butcher or soldier than a theologian. Many saw him as a charlatan, and used the nicknames pert and fop to express their contempt for his audacity and vanity.

On the other hand Karlstadt had a poor memory, depended on his notes, got embarrassed and confused. Eck won easily. Then, according to Luther, Eck came to me in my lodgings. He said he had learned that I had refused to debate. Luther answered,

How can I debate if I can't secure a safe conduct from Duke George? Eck responded,

I came here to debate with you, and if I can't, then I don't want to debate with Karlstadt either. What if I get a safe conduct for you? Will you debate with me then? Luther told him,

Get it and I will. Luther stated,

He left, and shortly thereafter I too got a safe conduct and so had the opportunity of debating. Eck expanded the items for debate to include the existence of purgatory, the sale of indulgences, the need for and methods of penance, and the legitimacy of papal authority.

Luther was superior to Eck in knowledge of the Bible, originality and depth of thought, while Eck knew history. Eck directly charged Luther with undermining the authority of the pope and of being a follower of Jan Hus, a Czech priest who was burned at the stake in July 1415 for denouncing the moral failings of clergy, bishops, and the papacy from his pulpit, and speaking out against indulgences. Luther reminded the audience that the early church showed no special regard to the bishop of Rome, and that the Greek orthodox church rejected any claim of Roman supremacy. In the process, Luther had to admit that in some important matters he did agree with Hus. Popes and councils can make mistakes, and scripture supports many of the teachings for which Hus was burned. Eck skillfully moved the debate to his advantage, forcing Luther to directly challenge papal authority, a claim that the Church had followed since 1302 when Pope Boniface VIII stated: We declare, state, define and pronounce that it is altogether necessary for salvation for every human creature to be subject to the Roman Pontiff. Luther asserted that scripture alone was the basis of Christian belief, that the Pope did not have the exclusive right to interpret scripture and that neither Popes nor church councils were infallible. Luther denied that membership in the Roman Catholic Church was necessary for salvation. He condemned the sale of indulgences to reduce time in purgatory, as purgatory was not mentioned in the Bible and that the Pope had no power because there was no mention of him in the Bible.Melanchthon was present at the first serious debate at Leipzig between Luther and the Roman Catholic supporter Johannes Eck. During the debate Philipp Melanchthon, also a spectator, wrote notes to Luther citing Bible passages contradicting papal authority.

Eck prodded Luther to state that even general councils can be in error when they promoted opinions that do not concern faith. This admission was perceived by the audience as damaging to Luther's cause. The Presider of the debate, Peter Mosellanus, described Luther's appearance:

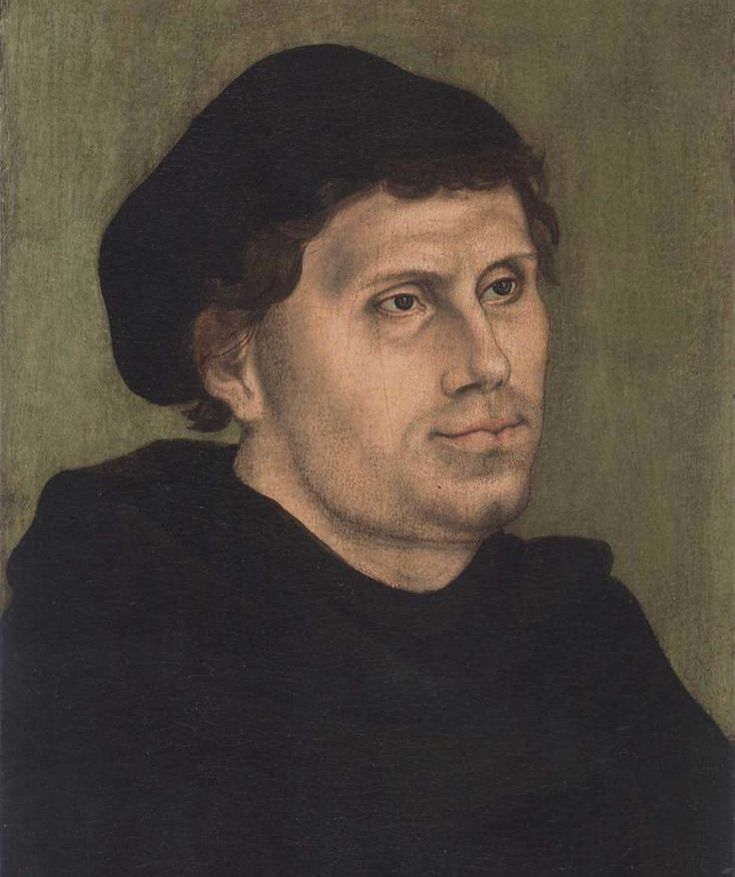

Luther is of middle stature, his body thin and so wasted by care and study that nearly all his bones may be counted. He is in the prime of his life. His voice is clear and melodious. His learning and his knowledge of Scripture are so extraordinary that he has nearly everything at his fingers' ends. Greek and Hebrew he understands sufficiently well to give his judgment on interpretations. For conversation, he has a rich store of subjects at his command; a vast forest of thoughts and words is at his disposal. He is polite and clever. There is nothing stoical, nothing supercilious, about him; and he understands how to adapt himself to different persons and times. He is lively and agreeable. He is always fresh, cheerful and at his ease, and has pleasant countenance, however his enemies my threaten him, so that one cannot believe that heaven is with him in his great undertaking. Luther said about Eck:

I am sorry that the learned doctor only dips into the Scripture as the water-spider into the water, that he seems to flee from it as the devil to the cross. I prefer the authority of Scripture. June 28, 1519 - While the debate in Leipzig continued Charles I, the 19-year-old king of Spain, defeated the candidacy of Francis I of France (Elector Frederick voted against himself) and was elected Holy Roman Emperor, succeeding his grandfather Maximilian I. He took the title Charles V.

July 4, 1519 – Indulgence seller Johann Tetzel died at the Dominican monastery in Leipzig. Earlier that year Luther wrote a letter in which he tried to console him by stating, The agitation was not your creation. The child had an entirely different father. July 14, 1519 – The Leipzig Debate concluded. Luther regarded it as a waste of time and he was convinced that Eck had won. But he made a deep impression on many students who left the university in Leipzig for Wittenberg.

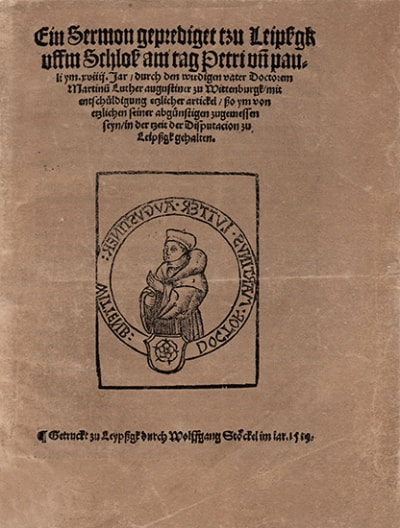

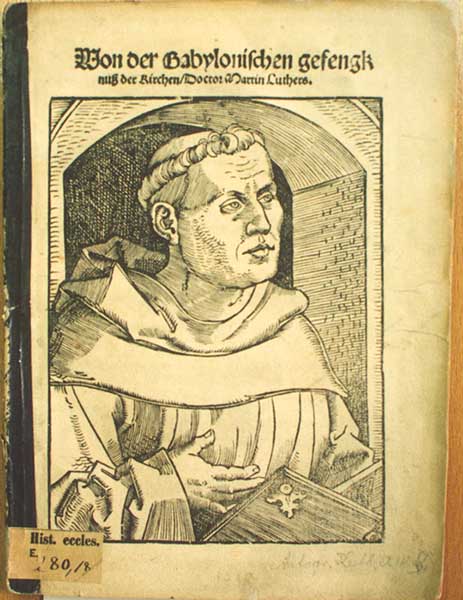

The Luther-Rome dispute grew and Luther's ideas became difficult to ignore. During the debate a scornful Eck applied a new name to those who criticized Rome. He called them "Lutherans," as an insult. Luther was horrified that any church would be named after him. He preferred "evangelical," from the Greek euangelion "belonging to the Gospel." With the debate concluded, Dr. Eck traveled to Rome to secure the condemnation of Luther and his followers. 1519 (after the Leipzig Disputation) - Master printer Wolfgang Stöckel in Leipzig published Luther’s speeches from the debate with Eck showing a woodcut depicting the reformer on the front page. This first picture of him also includes a rose. From then on the rose was known as Luther’s emblem, and from 1530 he used it (with a heart and a cross at its center) as his seal. At the same time the rose came to be seen as the symbol of Protestant Lutheran teaching and its church and formed part of many coats of arms.

When Martin Luther came to Leipzig in 1519 for the Disputation with Eck, he stayed at the home of master printer Melchior Lotter. In the same year, at Luther's urging, Lotter set up a branch of his business in Wittenberg, managed by his sons Melchior the Younger and Michael. Melchior Lotter was a friend of the reformer and sympathized with his ideas. He stands out among the Leipzig printers, having published more than 160 of Luther’s writings.

August 10, 1519 - Five ships under the command of Ferdinand Magellan of Spain embarked on an attempt to sail around the world.

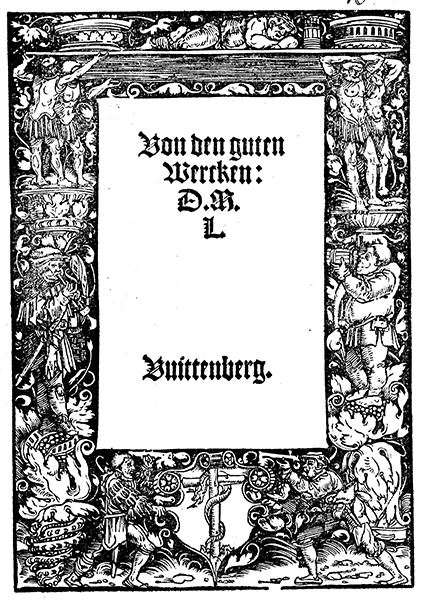

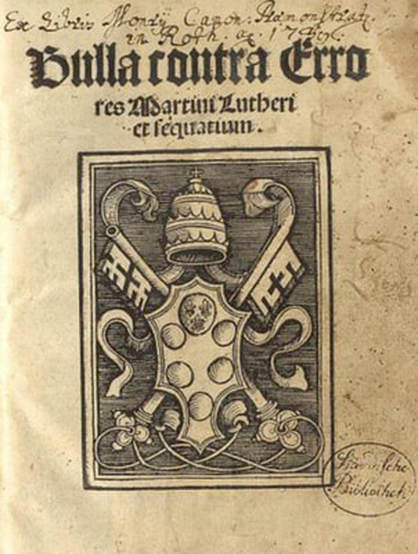

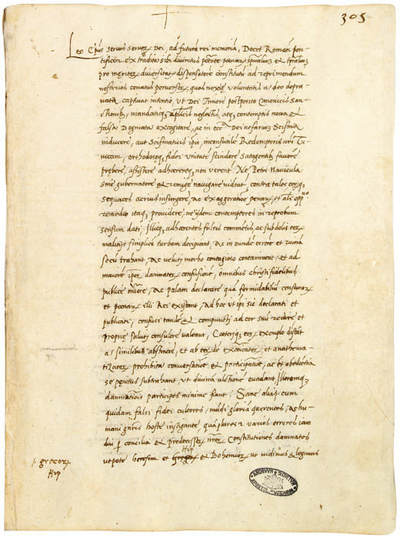

Early October 1519 - Luther declared himself to be in fundamental agreement with Jan Hus, who advocated church reform a century earlier in Bohemia, but was burned at the stake for his efforts, despite a promise of safe conduct.. 1520 (age 36) - Luther began an intensive period of writing. He also completed A Brief Form of the Ten Commandments, A Brief Form of the Creed and A Brief Form of the Lord's Prayer, which he believed contained the essentials for salvation as revealed in the Bible. Growth of the Printing Industry in the German States By 1520 and Cologne, Nuremberg, Strasbourg, Basel, Wittenberg and Augsburg were the leading publishing centers. With the exception of Cologne, which remained Catholic, the presses of these towns became the nerve centers of the Evangelical media campaign, flooding the cities of the empire with aggressive little pamphlets advocating reform. The Reformation perfected the use of the small booklet or pamphlet as a propaganda tool. Frequently made up of sheets folded twice to make four leaves or eight pages—and without a hard cover. These pamphlets were handy, relatively cheap, readily concealed and transported, and accordingly well-suited for delivering their message to a large audience. They could be easily transported by itinerant peddlers, hawked on street corners and in taverns, advertised with jingles and intriguing title pages, and swiftly hidden in a pack or under a coat away from prying eyes. Without these booklets, the thoughts and ideas of Martin Luther could never have developed such a reputation and allure - in this, historians agree. In the 16th century booklets, leaflets and tracts took over as the new mass media coverage for reporting, and created a level of publicity unknown up until then. As for the printing of Luther's publications: In 1518 not quite half of the printings were in German. In 1519 this figure rose to over six in ten, then in 1520 and 1521 around eight in ten, and for the rest of the decade around nine in ten. The most massive printing and reprinting of Luther's works came in the pioneering years of the Reformation movement. Half of the printings appeared by 1525 and three-quarters by 1530. Over eighteen hundred printings of Luther's works flowed from the presses by the end of 1525. An additional five hundred printings appeared by the end of the decade and eighty-five percent of these were in German. January 9, 1520 - After a delay caused by the election of Emperor Charles V, Rome restarted the inquisition against Luther and his ideas. March 15, 1520 - A letter was sent to Johann Staupitz, the vicar of Luther's monastic order, ordering him to restrain Luther or be dismissed. Two months later Staupitz resigned his position. He joined the Benedictines in 1522, and became Abbot of St. Peter's, Salzburg. May 1520 - Luther wrote his Treatise on Good Works. The first and highest, the most precious of all good works is faith in Christ, as he says, John 6. When the Jews asked Him: "What shall we do that we may work the works of God?" He answered: "This is the work of God, that you believe on him whom he hath sent." When we hear or preach this word, we hasten over it and deem it a very little thing and easy to do, whereas we ought here to pause a long time and to ponder it well. June 15, 1520 - Pope Leo X issued another bull against Luther. Printed copies bore the Latin title Bulla contra errores Martini Lutheri et sequacium (Bull against the errors of Martin Luther and his followers), but it is more commonly known as Exsurge Domine (Arise O Lord). It warned Luther that he will be excommunicated unless he recanted 41 sentences included in his 95 Theses within sixty days after publication of the bull in Saxony. The bull opened with a paragraph that compared Luther to a wild boar:

Arise, O Lord, and judge your own cause. Remember your reproaches to those who are filled with foolishness all through the day. Listen to our prayers, for foxes have arisen seeking to destroy the vineyard whose winepress you alone have trod. When you were about to ascend to your Father, you committed the care, rule, and administration of the vineyard, an image of the triumphant church, to Peter, as the head and your vicar and his successors. The wild boar from the forest seeks to destroy it and every wild beast feeds upon it Luther had 60 days commencing from the publication of the bull in Saxony to recant or face excommunication. In Catholic doctrine, in which salvation is only available through the church, excommunication amounted to eternal damnation. The bull also contained a directive forbidding any use of Luther's works and decreeing that they should be burned "publicly and solemnly in the presence and the clerics and people."

Johann Eck and Cardinal Aleandro were assigned to publish the bull in Saxony and its neighboring regions. This proved to be a mistake. While Eck and the Catholics had claimed victory at the Leipzig debate, Luther was extremely popular. Eck was Luther’s enemy and thus extremely unpopular. The bull was resisted in large parts of Germany. At Erfurt, students who sympathized with Luther tossed copies of the bull into the local river and at Torgau, a posted copy was torn down and defaced. Even some Catholic bishops hesitated as much as six months before publishing the bull's contents. At times, the opposition faced by Eck and Aleandro was so fierce that their very lives were endangered. At Leipzig, Eck had to retreat for an hour to a monastery in fear for his life.

In the meantime, Luther drafted an appeal of his case and sent it to the newly elected emperor Charles V. Often called An Appeal to Caesar, Luther asked the emperor to allow his guilt or innocence on the charge of heresy be determined after a hearing by non-church officials. For three years I have sought peace in vain. I have now but one recourse. I appeal to Caesar. I have no desire to be defended if I am found to be impious or heretical. One thing I ask, that neither truth nor error be condemned unheard and unrefuted. June 26, 1520 - In response to a treatise, in German, by Franciscan monk Augustine von Alveld of Leipzig, Luther published On the Papacy in Rome (Vom Papsttum zu Rom), his first major publication on the nature of the church. Alveld felt it was his duty to refute Luther and defend the papacy. He stated that it was foolish to argue against the authority of Rome and its jurisdiction over the entire church. A furious Luther wrote:

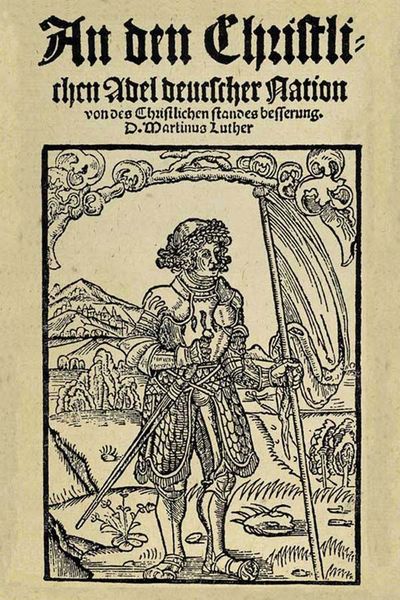

This, then, is the matter in question: Whether the papacy in Rome, possessing the actual power over all of Christiandom, as they say, is derived from divine or from human order ... No one says "I believe in the Holy Spirit, one holy Roman church, the communion of Romans ... when [Christ] said to Peter three times, "Tend my sheep," he had previously asked him three times whether he really loved him; and Peter answered three times that he loved him. So it is clear that where there is no love there is no tending. The papacy must be love or it is not tending [the sheep] ... no one can tend the sheep unless he loves Christ ... I only ask that anyone who wants to get at me should be armed with Scripture... IAugust 1520 - Luther published To the Christian Nobility of the German Nation (An den Christlichen Adel Deutscher Nation), the first of three major publications summarizing his views. It was written in German rather than Latin. He attacked the three walls erected by the Roman church to protect itself from reform:

September 1520 - Luther wrote the second of his major 1520 publications, The Babylonian Captivity of the Church (De Captivitate Babylonica), in which he compared the captivity of the church by Rome to the captivity of the Jews in Babylon in 597 BC. Luther declared that the one authority, one test for everything, is the Word of God, whereas the papacy has held the church of God captive under the traditions and commandments of men. The church should have only two sacraments: baptism and the Lord's Supper. The other so-called sacraments are merely ceremonies instituted by man. He argued that transubstantiation (the process by which the bread and wine in communion are said, according to Catholic teaching, to miraculously become the actual body and blood of Christ) and the mass as a sacrifice of Christ on the altar as a way of appeasing God, were false teachings. Angry in tone, it was the first time Luther forthrightly accused the Pope of being the Antichrist. It set Luther irrevocably against Rome.

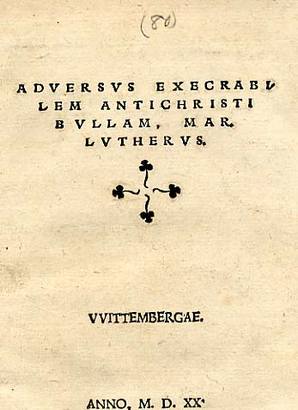

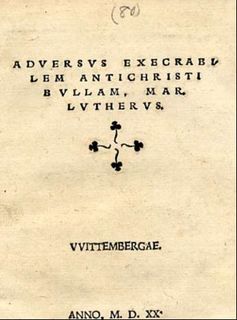

October 10, 1520 - After three months Luther finally received the papal bull, He composed a response entitled Against the Execrable Bull of Antichrist (Adversus Execrabile Antichristi Bullam): ...whoever wrote this bull, he is Antichrist. I protest before God, our Lord Jesus … that with my whole heart I dissent from the damnation of this bull, that I curse and execrate it as sacrilege and blasphemy of Christ, God's Son and our Lord. This be my recantation, O bull, thou daughter of bulls... Let them show where I am a heretic, or dry up their spittle. Mid-October 1520 - At the University of Erfurt, students threw a copy of the papal bull into the Elbe River, calling it by the Latin word bulla (meaning bubble). “It is only a bubble,” they said, “let it float on the water.” University officials took no action against them.

November 12, 1520 - Luther's books were burned in Cologne. Burning of his books in other cities followed shortly thereafter. November 20, 1520 - Undaunted, Luther wrote the third of his major 1520 writings, Freedom of the Christian (Latin: De Libertate Christiana; German: Von der Freiheit eines Christenmenschen), sometimes called A Treatise on Christian Liberty. It was written in both German and Latin and, unlike his other two major books published that year, its style and language were uplifting, reassuring: A Christian is a free lord, subject to none. A Christian is a perfectly dutiful servant, subject to all ... We are justified (made right with God) by faith alone; salvation cannot be earned by good works. Good works follow from that faith. The tree bears fruit, the fruit does not bear the tree. Luther attached a copy to an open letter of apology to Pope Leo X:

I understand that I am accused of great rashness, and that this rashness is said to be my great fault, in which, they say, I have not spared even your person. For my part, I will openly confess that I know I have only spoken good and honorable things of you whenever I have made mention of your name ... I have truly despised your see, which is called the court of Rome. Neither you nor anyone else can deny that it is more corrupt than any Babylon or Sodom ever was. As far as I can see, it is marked a completely depraved, hopeless, and notorious godlessness ... You would all perish by poison, before you could undertake to decide on a remedy. It is all over with the Court of Rome; the wrath of God has come upon her to the uttermost. She hates councils, she dreads to be reformed... November 29, 1520 – Luther published a second response to the papal bull Exsurge Domine entitled Assertion of All the Articles Wrongly Condemned in the Roman Bull:

Wherefore I, Doctor Martin Luther by name, have undertaken, with joyful heart, to prove by Scripture all the articles, for the further instruction and the exposure of the false and pretended Church, so that everyone may be able to protect himself against the blind feints that these tricksters are wont to make. Perhaps even they will sometime come to themselves and consent to exchange their hypocrisy for truth, their trickery for serious earnest, their pretensions for proofs. December 10, 1520 - Luther and Melanchthon invited the faculty and students of Wittenberg University to assemble at Wittenberg's Elster Gate. A bonfire was lit and Luther burned his copy of the bull Exsurge Domine and other papal documents, including books of church law and books written by his enemies. Luther later explained his actions.

Since they have burned my books, I burn theirs. The canon law was included because it makes the pope a god on earth. So far I have merely fooled with this business of the pope. All my articles condemned by Antichrist are Christian. Seldom has the pope overcome anyone with Scripture and with reason. January 3, 1521 (age 37) - Luther was excommunicated by a third bull, Bull against the errors of Martin Luther and his followers (Bulla contra errores Martini Lutheri et sequacium), but it is more commonly known as Exsurge Domine (Arise O Lord).

It gives us grievous sorrow and perplexity to say this: the slave of a depraved mind, has scorned to revoke his errors within the prescribed interval and to send us word of such revocation, or to come to us himself; nay, like a stone of stumbling, he has feared not to write and preach worse things than before against us and this Holy See and the Catholic faith, and to lead others on to do the same. He has now been declared a heretic.

A Diet at Worms

January 1521 - The Diet ("dee-it" from Latin dies, meaning "day"), at the ancient city of Worms (pronounced "vorms") in southwest Germany.was convened, the first real test of the recently elected 20-year-old emperor Charles V.

February 1521 - Elector Frederick III of Saxony, where Luther lived, believed Luther was being treated unfairly. He reminded emperor Charles that the constitution of the empire, which he signed at his coronation, said that no German would be taken out of Germany for trial. March 1, 1521 - In a pamphlet published in German, Luther said: The Pope is more wicked than all devils; for he damned the faith, which no devil had ever done. Therefore, because I call the Pope the greatest murderer that has ever been since the beginning of the world, in that he kills souls as well as bodies, I am, God be praised, a heretic. March 6, 1521 - Emperor Charles V, a devout and loyal subject of the Roman Church, summoned Luther to appear before the Diet of Worms. He promised him safe conduct. Before the assembled princes, nobles, bishops and the emperor himself, Luther faced his greatest challenge. The traditions and practices of a millennium were there to judge him.

April 2, 1521 - Luther began the journey to Worms accompanied by his friend and colleague Nicolaus von Amsdorf, Peter Swaven (a Danish student) and Johann Pezensteiner (a fellow Augustinian). Philipp Melanchthon wanted to accompany his friend but was needed at home. Luther told him, If I do not return and my enemies murder me, I implore you, dear brother, to persevere in teaching the truth. Do my work during my absence ... You can do it better than I. In you the Lord has a more learned champion. Justus Jonas, at that time a professor at Leipzig, joined the company in Weimar. It took Luther 14 days to travel 322 miles in an open farmer's wagon, with stops along the way to preach to large, enthusiastic crowds in Leipzig, Erfurt, Eisenach, Gotha and Frankfurt. As Luther approached Worms he was warned to hurry back to Wittenberg. He answered:

Though there was as many devils in Worms as there are tiles on the roofs, I will go there. A few days before his death in Eisleben, he described his feelings as he pushed forward to Worms:

I was fearless, I was afraid of nothing; God can make one so desperately bold. I know not whether I could be so cheerful now. April 16, 1521 - Luther entered Worms in a triumphal procession. A large crowd gathered to cheer him. The people were just as excited to see him as they were the 21-year-old Emperor Charles V. Rough estimates suggest that around 7,000 people lived in Worms at the start of the 16th century. Almost twice as many visitors to the Imperial Diet had descended on the city since January 1521. The number exceeded expectations by far, and it soon became clear that the preliminary planning had been inadequate. Food was expensive and accommodation was hard to find. Luther found lodgings in the Seminary of St John. Over the next ten days, a constant procession of visitors descended on the room that Luther had to share with two other men.

April 17, 1521 - First hearing of the Diet of Worms began. It took place in the Bishop's Palace where Emperor Charles was residing, rather than the town hall and the house 'Zur Münze' (Guildhall) where the actual affairs of the Imperial Diet were negotiated. Spanish representatives at Luther's hearing described the low, cramped room chosen for the hearing, Luther's enemies were numerous and powerful, and eager for his destruction: Emperor Charles V, the archduke Ferdinand, six electors, twenty-four dukes, eight margraves, thirty bishops, and other princes and prelates of the realm — the most remarkable assembly ever convened against one man. Johann Eck (not the same man who debated Luther in Leipzig, but an assistant of the Archbishop of Trier), acted as spokesman for the emperor. He asked in both German and Latin if a collection of about 25 writings displayed on a table was Luther's and if he was ready to acknowledge their heresies. Luther's colleague and advocate, Dr. Schurf, stood beside him and demanded that the titles be read aloud, which was done. The documents probably included the 95 Theses, Resolutions Concerning the 95 Theses, On the Papacy at Rome, Address to the Christian Nobility, The Babylonian Captivity of the Church and On the Freedom of a Christian. Luther requested more time for a proper answer, and was given until the next day. April 18, 1521 - The second day of the hearing was moved to larger chambers to accommodate the sizable audience, Luther entered the hall at 4 pm. He was forced to wait outside the hall for two hours as the Emperor was otherwise occupied. Eck asked Luther in Latin and German whether he would acknowledge all his writings or recant some part. Luther said the books piled on the table were all his, but they were not of one sort. He then divided his books into three types:

Unless I am convicted by Scripture and plain reason, I do not accept the authority of popes and councils, for they have contradicted each other, my conscience is captive to the Word of God. I cannot and I will not recant anything, for to go against conscience is neither right nor safe. According to tradition, he concluded his statement with the often quoted words:

Here I stand. I can do no other. God help me. Amen. The emperor broke up the session of the Diet at 8 PM amid confusion. Upon reaching his lodging place Luther threw up his arms and exclaimed,

I am through, I am through! April 24, 1521 - Elector Frederick the Wise informed his brother John about his decision to support Luther.

April 25, 1521 - Diet of Worms was dismissed. April 26, 1521 - Luther left Worms with the men who traveled to the Diet with him, stopping at Möhra, the Luder ancestral home, to visit his relatives. "My Patmos" May 4, 1521 - At Altenstein, in the Thuringian forest, Luther's carriage was halted by armed horsemen. Elector Frederick the Wise, who left the Diet of Worms early because of illness, anticipated the outcome and arranged Luther's "abduction." Luther was seized and taken to the Wartburg, a fortress overlooking Eisenach. Only a few trusted men knew where he was kept. Not even John, the brother of Elector Frederick, was aware of Luther's location. Rumors spread that he was imprisoned and cruelty treated Some feared that he had been murdered, including the German painter Albrecht Durer, who grieved,

O God, if Luther be dead, who would proclaim the holy gospel so clearly to us? Luther hid at the Wartburg for 11 months (May 1521 to March 1522) during which time he grew his hair and a beard and called himself Junker Jorg (Knight George). He referred to the ancient castle, founded c.1067, as "my Patmos."

They have taken away my habit and dressed me in houseman's apparel. I am letting my hair and beard grow. You would be hard put to recognize me, for I no longer recognized myself. I live in Christian liberty, free from all the laws of that tyrant. At the Wartburg Luther was provided a room to continue his studies and writing. He stayed in touch with events in Wittenberg, writing over 44 letters to friends, colleagues and others. In May 1521 he wrote to his friend George Spalatin: "I have nothing to do here and sit around all day as if in a daze. I am reading the Greek and the Hebrew Bibles."

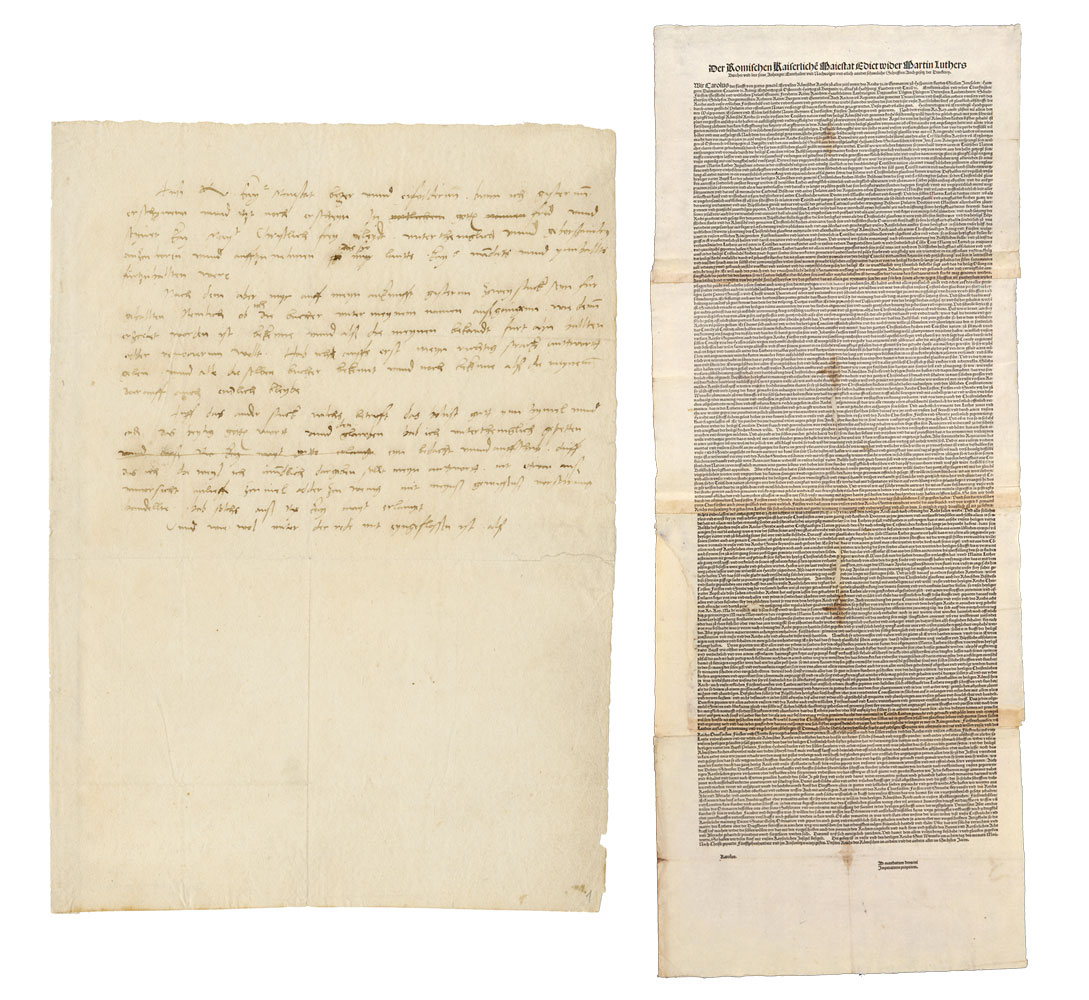

Luther showed his gentler side when he wrote of enjoying the singing birds, "sweetly lauding God day and night with all their strength." Exulting in the beauty of the nighttime sky he said: "He who has built such a vault without pillars must be a master workman!" He also penned many sermons (more like sermon starters) to help preachers reflect on biblical texts. four major papers (On Monastic Vows, On the Abolition of Private Masses and Address to the German Nobility), commentaries on the psalms and the Magnificat (the song of Mary). But life at the Wartburg was not as rosy as some letters implied. He was ill for months. To Nicholas von Amsdorf at Wittenberg he wrote: "My constipation is bad!" Luther also suffered loneliness and depression. Legend says that while working in his study at the Wartburg Luther threw an inkwell at the devil. April 1521 - While Luther was secluded at the Wartburg, Philipp Melanchthon completed writing his Loci Communes Theologici (Theological Commonplaces), his highly influential explanation of Protestant theology based on his lectures on St. Paul's letter to the Romans. It was the first systematic treatment of Reformation thought on sin, law, gospel, grace, free will, justification and faith, the distinction between the Old and New Testaments, signs, charity, the magistrates, and scandal. Drawing on scripture, Melanchthon argued that the individual human cannot resolve to do good works and earn merit before God. But God’s grace consoles man with forgiveness, and man’s works, though imperfect, are a response in gratitude to God's benevolence. Luther declared that Common Places deserved a place in the canon of the Bible; the University of Cambridge in England later made it required reading, and Queen Elizabeth I virtually memorized it so she could converse about theology.Drawing on scripture, Melanchthon argued that the individual human cannot resolve to do good works and earn merit before God. But God’s grace consoles man with forgiveness, and man’s works, though imperfect, are a response in gratitude to God's benevolence. Luther declared that Common Places deserved a place in the canon of the Bible; the University of Cambridge in England later made it required reading, and Queen Elizabeth I virtually memorized it so she could converse about theology. We must seek the truth, love it, defend it, and hand it down uncorrupted to our posterity. May 25, 1521 - Edict of Worms was finally signed by emperor Charles. It called Luther a devil in monk's clothing and accused him of destroying the sacraments and encouraging war, murder, robbery and other crimes.

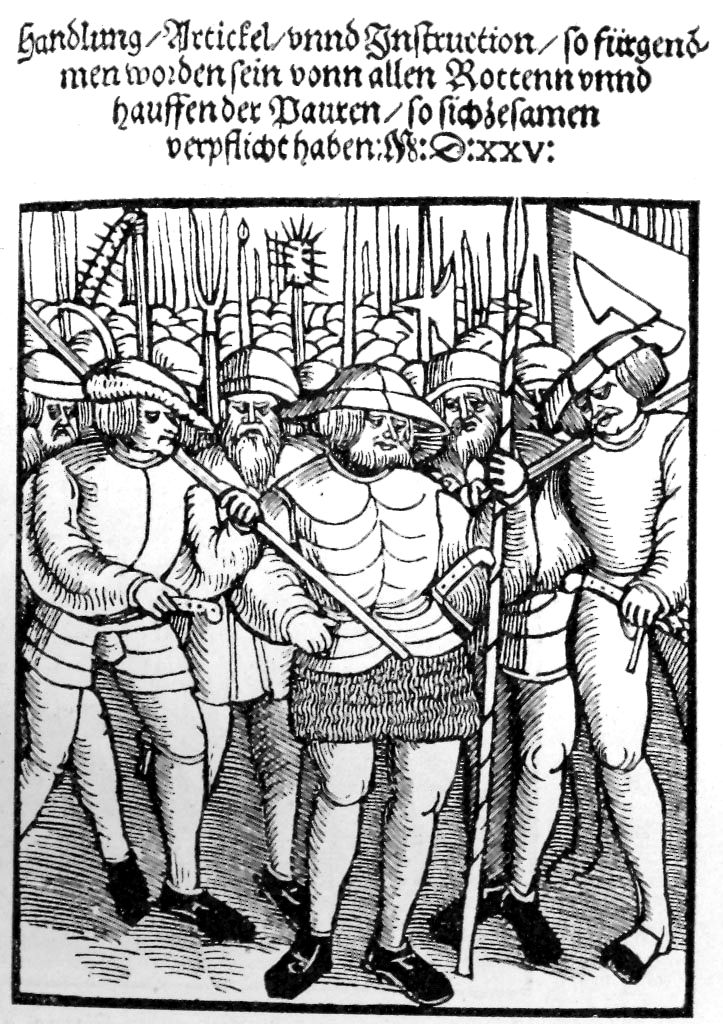

We forbid anyone from this time forward to dare, either by words or by deeds, to receive, defend, sustain, or favour the said Martin Luther. On the contrary, we want him to be apprehended and punished as a notorious heretic, as he deserves, to be brought personally before us, or to be securely guarded until those who have captured him inform us, whereupon we will order the appropriate manner of proceeding against the said Luther. Those who will help in his capture will be rewarded generously for their good work. Reform Evolves to Insurrection

June 1521 – During Luther’s absence, leadership of the reform cause in Wittenberg passed to Philipp Melanchthon and Andreas Karlstadt. Rather than slowing down, the pace of reform quickened. Karlstadt, a professor and archdeacon at the Castle Church, a man of learning and zeal, but radical, injudicious and ambitious for leadership, performed the first reformed communion service. He did not elevate the elements of communion, wore street clothing during the service, and purged all references to sacrifice from the traditional mass. He shouted the words of institution ("This is my body....", etc.) in German rather than whispering them in Latin, declared that confession before communion was unnecessary and he let the people take both the bread and wine on their own during the Communion. On a more radical level Karlstadt maintained that no priest should be appointed unless he had a wife and children. He also taught that sculptures and paintings were dumb idols, forbidden by the second commandment (which led to widespread destruction of altars and images). Beginning of September 1521 - To solve his financial problems Albrecht of Mainz published a bull promising an indulgence to anyone who paid to visit his huge collection of 9,000 relics at the Stiftskirche in Halle. Luther saw the resumption of indulgence sales as a slap in the face by the archbishop for whom the pope had issued the indulgence that led to Luther's ninety-five theses. The news stirred Luther to write a pamphlet, Against The New Idol at Halle. However, Luther later learned that Elector Frederick wouldn't allow him to publish it. The Elector said,

I will not suffer Luther to write against the archbishop of Mainz, and thus trouble the public peace. Luther was indignant! But he agreed to delay it and allow Philipp Melanchthon to edit out some of his more offensive expressions. Then, on December 1, 1521, he wrote a letter from the Wartburg directly to Albrecht:

Your electoral highness has again set up in Halle the idol which devours at once the money and the souls of poor Christians...it is my humble prayer that your eternal highness would call to mind how this affair began, and how, from a mere spark, there burst forth a terrible flame...If the idol is not taken down, it is my duty to make a public attack on your highness as I attacked the pope himself. Let your highness act now.. I look for a prompt and favorable reply in 14 days.. Albrecht responded to Luther:

My dear doctor, I have received and read your letter and I've taken it to be well-intended. But the cause that induced you to write me no longer exists. I desire, with the assistance of God, to conduct myself as a pious bishop and a Christian brother, and I have knowledge that the grace of God is necessary for my guidance ... I know how to receive the rebuke of a Christian brother. By my own hand. Albrecht Albrecht yielded as a matter of policy and because no other recourse was open to him.

November or December 1521 - Luther began translating the New Testament into German so that all his countrymen could read the word of God for themselves. He translated from the Greek text, using Erasmus' second edition (1519) of the Greek New Testament, known as the Textus Receptus. Luther did not translate from the Latin Vulgate, the Latin translation officially used by the Roman Catholic Church. Like Erasmus, Luther learned Greek at the Latin schools led by the Brethren of the Common Life, who added Greek as a new subject to their curriculum in the late 15th century. To aid his work Luther went into nearby towns and markets to listen to people speak, so the butcher and baker could understand the scriptures.

November 1521 - Luther published The Judgment of Martin Luther on Monastic Vows. He assured monks and nuns that they could break their vows without sin, because vows were an illegitimate and vain attempt to win salvation. Thirty of the forty monks remaining in the Augustinian monastery at Wittenberg left in a disorderly manner. Among them was Gabriel Zwilling who preached in the parish church in Luther's absence. He fiercely attacked the mass, the adoration of the sacrament and the monastic system as dangerous to salvation. December 1, 1521 - Pope Leo X died of malaria, so suddenly that the last sacraments could not be administered; contemporary suspicions of poison were unfounded. He was succeeded by Adrian Florenszoon Boeyens, who took the name Adrian VI.

December 3, 1521 - Angered by the violence and destruction in the name of reform, Luther secretly left the Wartburg and returned to Wittenberg, still disguised as Junker Jorg. He spent three days in the home of Amsdorf, not daring to be seen in public. Though pleased that the people were receiving both bread and wine at communion, he didn't approve of the destructive acts. Back at the Wartburg he wrote A Sincere Admonition by Martin Luther to All Christians to Guard Against Insurrection and Rebellion. After Christmas 1521 - The situation in Wittenberg became even more volatile with the arrival of three zealots — Nicholas Storch, Thomas Drechsel and Marcus Stubner — from Zwickau (64 miles to the south). Philipp Melanchthon was alarmed by the ideas of the so-called Zwichau Prophets, especially on baptism. Like the Anabaptists (literally "baptize again") the "prophets" taught that people should only be baptized as adults, when they fully understood the meaning of the sacrament. Anyone baptized as an infant must be baptized again. They boasted of visions and direct communication with God and the Angel Gabriel and also held the Bible was secondary to dreams and revelations and that Christ's return was imminent. Many in Wittenberg were swayed by their teachings. These efforts to put reform into practice generated protests that threatened to undermine law and order. January 19, 1521 - Karlstadt married Anna von Mochau, the fifteen-year-old daughter of a poor nobleman, asserting that priests should be allowed to marry. Others left their monasteries to follow his example. Some were arrested. Luther said he was "pleased over Karlstadt's marriage, I know the girl." March 1522 – Luther completed the first draft of his New Testament translation. Remarkably, it took him only 11 weeks! March 6, 1522 - At grave risk to himself because of the Edict of Worms, Luther chose to come out of hiding. Luther’s attitude toward the reforms instituted in Wittenburg by Karlstadt and others was conservative. He did not believe that change should occur hurriedly. His notion was to “make haste slowly,” The 175 mile, 8-day journey to Wittenberg took him first to Jena (about 66 miles from Eisenach) where, still disguised as Knight George, he lodged at the Black Bear Inn (now the Hotel Schwarzer Bar).

That night Luther, dressed in a red beret, plain doublet and hose, with a sword at his side, settled in for a mug of beer, his favored beverage. As he thumbed through his Psalter he fell into a conversation with a pair of Swiss divinity students -- Johann Kessler and Wolfgang Spengler -- who, coincidentally were on their way to Wittenberg for further their religious studies and were hoping to meet the great Martin Luther. Luther encouraged them to study Hebrew and Greek if they wanted to understand the Bible. One of the students later wrote: "His eyes were black and deep. They sparkled and flashed like a star, so that they could not easily be met." Luther asked them: "What do the Swiss think of Luther?" They replied that some regard him highly, others see him as a dangerous heretic. The generous "knight" paid the students' bill and they asked him if he knew whether Luther was in Wittenberg. Luther said, "I know positively that he is not there, but he soon will be." From Jena he made his way to Borna (another 59 miles), arriving on March 5. He halted his journey long enough at the residence of his escort to write a second letter to his ruler and protector, Elector of Saxony Frederick the Wise in which he justified his reasons for leaving Wartburg Castle against the will of the Elector and referred to himself as a free man due to his faith in God. He wrote: Events that have taken place at Wittenberg, to the great reproach of the gospel, have caused me such pain…I want to let you know that I am going to Wittenberg under a protection far higher than that of princes and electors. I have no need for your help…this is a matter which requires neither sage counsel's, nor the edge of the sword. God alone is my master and my protector. In disobeying your instructions, I relieve you, in the sight of God, from all responsibility, should I be thrown into prison, or be deprived of life by the tyrants. If the emperor takes my life he alone will have to account for it...if they call upon you to lay your hands on me, obey them without taking heed of me, for I would not desire you to suffer on my account. Love and honor for God forever. Amen. Given at Borna this Ash Wednesday 1522. Your grace's humble servant, Martin Luther Luther left Borna the following day and arrived in Wittenberg on March 6. Elector Frederick wrote him a letter stating:

Let him address me a letter explaining the motives of his return, and let him say that he returned wholly without my permission. The day after his arrival at Wittenberg Luther responded to the elector's letter:

Satan, during my absence, has penetrated into my fold, and committed ravages there which my presence alone can repair. A letter would serve no purpose. I must make use of my own eyes to see and my own mouth to speak. My conscience will not permit me to delay. Beginning Sunday, March 9, 1522 (Invocavit Sunday; First Sunday of Lent) - Luther preached eight sermons on eight successive days, calling for calm and patience, reminding the citizens to trust God's word rather than resort to violence to bring about necessary change. In these short sermons Luther stressed some similarities with Karlstadt. Luther’s presence and his eight Invocavit Sermons, as they were called, succeeded in quelling the unrest in Wittenberg. Here are the key points in each:

1st Sermon on Sunday: There must ... be love ... for without love faith is nothing, as St. Paul says, 1 Corinthians 2:1, “If I could speak with the tongues of angels, and of the highest things in faith, and have not love, I am nothing” ... Let us beware lest Wittenberg become Capernaum. I notice that you have a great deal to say of the doctrine which is preached to you, of faith and of love. This is not surprising; an ass can almost intone the lessons, and why should you not be able to repeat the doctrines and formulas? Dear friends, the kingdom of God — and we are that kingdom — consists not in speech or in words, but in deeds, in works and exercises. God does not want hearers and repeaters of words, but doers and followers who exercise themselves in the faith that works by love. With order restored in Wittenberg, Luther restarted his academic duties at the University, he also delivered an address every week on the books of the Bible and every Sunday he preached a sermon in All Saints Church. He returned to the Black Cloister and resumed wearing his monk's cowl. but only for a couple more years.

Karlstadt agreed to seek a pastoral position elsewhere. Luther demanded that the Zwickau Prophets authenticate their message with a miracle, which they refused to give. They denounced Luther and left Wittenberg.

The Gospel Speaks German Luther brought the draft of his New Testament translation with him from the Wartburg. He refined it with the help of Philipp Melanchthon, Wittenberg University's resident Greek scholar, and others. By late spring of 1522 it was readied for publication. Using three presses, 3,000 copies of Luther's New Testament, Das Newe Testament Deutsch, were printed in secret and without his name. August 4, 1522 - Martin Luther wrote Contra Henricum Regem Anglicum in response to King Henry VIII of England's Defense of the Seven Sacraments. Neither subtle nor tactful, it cost him most of his support in England.

But when knowingly and designedly this damnable and offensive worm forges lies against the Majesty of my King in Heaven, it is right for me, on behalf of my King, to spatter his Anglican royal highness with his own mud and filth, and cast down and trample underfoot the crown that blasphemes Christ. September 1522 - Luther's German New Testament was distributed for sale. Known simply as the September Testament, it contained 222 pages. It promoted the understanding of the gospel and standardized the German language. Luther's translation was not literal in the truest sense of the word, because he wanted this Bible to be read aloud. Before any word or phrase could be put on paper, it had to be understood by the average German.